“Can psychedelics save the Jewish people?”

j. Weekly August 20,2019

When the rabbi begins with “I do not condone the use of psychoactive substances regulated by the FDA,” you know you’re in for something special.

Thus began Rabbi Zac Kamenetz’s Aug. 14 talk at Afikomen Judaica in Berkeley, titled “Psychedelic Research and the Future of Judaism.” Yes, please. Thank God for Berkeley.

Despite the far-out subject matter, Kamenetz, 37, has a rather establishment-y rabbinic job: Director of Jewish Living and Learning at the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco. He is disarming, warm and ready to answer any question about himself: about his spiritual path, his family — and, oh yeah, that time he was one of the subjects in a Johns Hopkins University study that dosed clergy of various traditions with psilocybin, the psychoactive compound found in Psilocybe mushrooms (aka magic mushrooms, shrooms, etc.).

The study, which is still ongoing with the results yet unpublished, recruited clergy to undergo psychedelic trips in controlled environments in the hope that people with pre-existing spiritual conceptual frameworks would have new ways of talking about psychedelic experiences.

One challenge facing people who do research on these substances — which have a variety of legitimate medical uses, mainly around mental health, such as healing from traumas, serious anxiety and clinical depression — is that our culture and our language lack adequate ways of describing the feelings and experiences that ensue.

Kamenetz first heard about the study from another rabbi who had been rejected from it. It seems that a large percentage of clergy who applied to participate were rabbis — but a large percentage of the clergy rejected from the study were also rabbis. One of the requirements was that subjects not have previous experiences with these substances. And, as it turns out, a large percentage of the rabbis who applied did not meet that criterion.

Kamenetz’s first trip took place in a comfortable room at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore with a couch and various religious symbols — a cross, a small statue of Buddha, etc. — and he was accompanied by a guide, one of the researchers. He put on a sleep mask and headphones outfitted with a playlist of classical music, was given a dose of psilocybin, and off he went.

Though it was his first psychedelic-assisted mystical experience, it was not Kamenetz’s first mystical experience.

That occurred in Israel, at Tel Gezer, during Kamenetz’s junior year of high school.

A tel is a mound that contains centuries of off-and-on human habitation. Tel Gezer is a breathtaking archaeological site about halfway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv (which, despite its name, is not a tel at all). There, you can stand in one spot and see thousands of years of human history all at once — dating back from the 4th century BCE all the way to the Arab village Abu Shusha, which was destroyed by Israeli forces in 1948.

“I had never experienced time that way before,” Kamenetz told me. “I felt a bolt of lighting. I felt like I had an encounter with the Divine that was unrehearsed and unmediated.”

At this point, I had to stop him to say that I, too, had an unexplainable experience at Tel Gezer during a high school semester in Israel.

In my experience, I told him, I felt time dilate as if thousands of years of human history were within reach all at once. It wasn’t a divine encounter (I think?), but it was certainly mystical, though I would’ve bristled at that word at the time.

“I became religious on the spot,” Kamenetz said. “I bought a kippah, I started reading ‘The Jewish Catalog,’ someone gave me a pair of tefillin — and I stole an ArtScroll siddur from the Kotel.” When he returned home to Southern California, he started walking every Shabbat to a Conservative synagogue and observing Shabbat and kashrut in his otherwise nonobservant household.

Years later, he had another mystical experience, this time on the Johns Hopkins couch.

The playlist blew his mind, as he considered the limitless genius of the composers. He saw the lights and swirling visions we often picture when we think of psychedelics. He gave birth to his daughter.

“I saw images of my wife and daughter, and I felt the release of oxytocin from my brain in incredible detail and how it went through my entire body, tears welling up, joy and gratitude,” he told me. “We had gone through two years of infertility. My daughter was only just born at the time. The intensity of love and gratitude that I felt for my wife and daughter was overwhelming.”

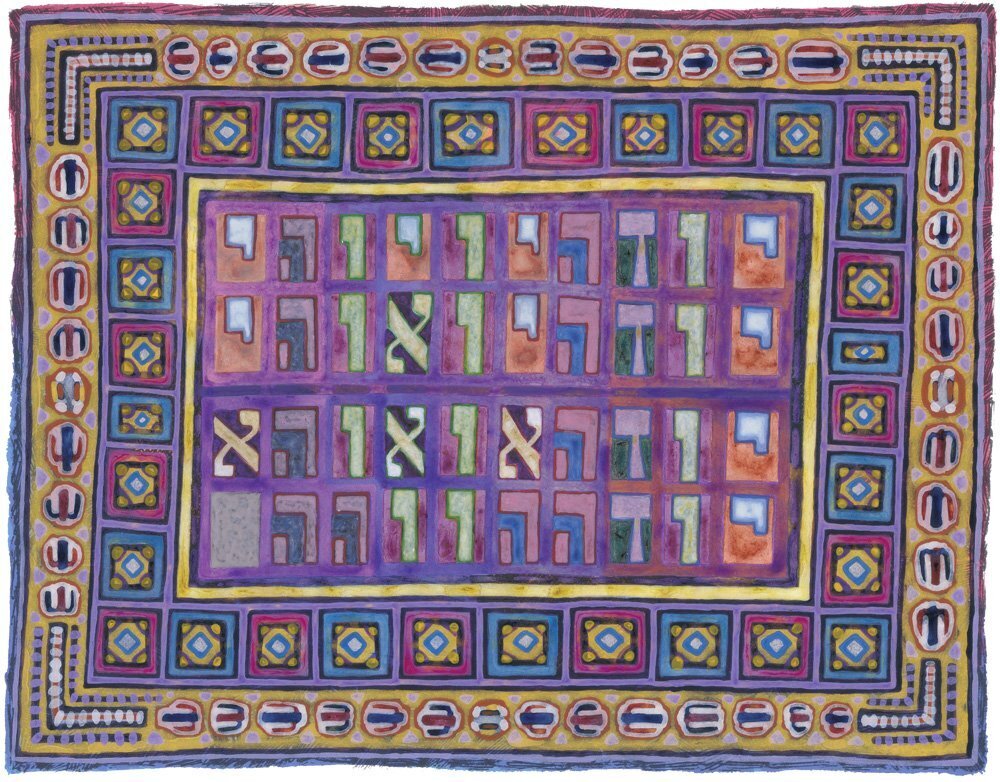

And there was one explicitly Jewish moment: “I had the image of a very large tree, where I saw these two branches of red and blue coming out from the trunk, the energy moving back and forth, from side to side, and I was able to immediately understand that this was about the integration between chesed and din — generosity/compassion and boundaries/power.”

It was as prototypical a Jewish mystical vision as possible, drawing on the kabbalistic Tree of Life, a diagram of God’s various attributes and qualities (called sefirot), including chesed and din, arranged loosely in the shape of a tree.

Six months later, the study required him to return for a second trip, this time with a higher dose of psilocybin.

“I expected more of the same, but bigger — bigger lights, bigger insights. Will I make contact with God?” Instead, it turned out to be an experience of nothingness.

“It was dark, there was no frame of reference inside, I felt like I was stuck in a hole with no light, I was incredibly bored and disappointed.”

When the experience was over, he was sad and upset. “I felt like I had failed.” But the researchers told him that the immediate experience of a trip isn’t necessarily the point. “It is also about the ongoing integration of the experiences, processing and reflecting over time,” Kamenetz said.

Now that he has read more about psychedelic experiences, “I’ve come to learn that this nothingness is a totally normal experience,” he told the Afikomen crowd of about 30 people.

“Yes, there is the bliss and color and light, but then there’s a higher reality that falls away to experiencing the void. In kabbalistic language, there is a point at which there is no imagery, no words, nothing that can be experienced,” he said. “We call that the Ein Sof, that which is without end.”

I asked him: Should more Jews try psychedelic substances? He hesitated, then said, “Should? I wouldn’t put it like that.”

His opening disclaimer about psychoactive substances aside, Kamenetz does have a nascent plan to bring the joy and healing of psychedelics to the Jewish people.

“The rational tradition has won out in American Jewish circles,” he said, visibly saddened by that fact. “Judaism as a vehicle for occasioning mystical experience seems to be a reality for very few American Jews.”

Kamenetz sees this as a big problem. So here’s his plan: “I would like to be the first rabbi to become certified as a psychedelic-assisted therapist.” Which, as it turns out, is a real thing. And, naturally, one can earn such a certification right here in the Bay Area, at the California Institute of Integrative Studies in San Francisco. Kamenetz is applying to be in the next cohort of students.

Beyond that, he has some big, if so far only half-formed ideas. He sees an entire new field of Jewish psychedelic research and experience.

“The idea that there is a non-ordinary state that you can learn from, heal from, experience the unity of all creation and maybe the divine — doesn’t seem to be on the forefront of current Jewish imagination,” he said.

But that doesn’t have to be true. Our tradition is not bereft of mysticism and esotericism. And Kamenetz wants to bring that to American Jews by establishing a place where they can try psychedelics in a Jewish context.

“Someday, I see a space, maybe in the East Bay, where people can have safe and supported psychedelic experiences individually, and then integrate those experiences in a community that is invested in the application of mystical experiences with other people. This is total science fiction because it doesn’t exist. Or it exists underground,” Kamenetz said.

“The last person to talk extensively about this in American Judaism was Reb Zalman” — Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, who founded the Jewish Renewal movement right here in the Bay Area at the height of the counterculture movement — “and that was a long time ago. He called MDMA [now known as the club drug ecstasy] just as sweet as Shabbos.”

I’ve long been psychedelic-curious, but also psychedelic-terrified. Temporary death of the ego? Sounds awful. Nevertheless, I’m sure my curiosity will someday get the better of me.

I hope by then Kamenetz and his someday-maybe-psychedelic-shul-ish-thing will be ready.

That so many rabbis were rejected from the study because they had already tried psychedelics tells Kamenetz that, “something is going on here, something indicative of a larger trend, and a longing among Jews for these experiences.”

Psychedelics increasingly are being used in clinical settings to heal intense psychological trauma. And the Jews, Kamenetz believes, could use some of that: “How can we understand years of exile, diaspora, anti-Semitism? How can we heal multi-generational traumas? Maybe through these substances, we can heal our people.”

In any case, Kamenetz admits that he’s still in the early stages of understanding his own trip experiences and the potential of psychedelics in the Jewish community.

As he learned from the study, “integration,” the process of making sense of psychedelic experiences and making them a part of one’s life in an ongoing way, is a lifelong process.

“You are part of my integration just by being here tonight,” he told the crowd at Afikomen.

By reading this column, I suspect you’re a part of it now, too.